Police Contacts in Denver and Boulder Counties: Celebrating 62%

Police Contacts: Why 62% Makes Us Excited

Written by Tennyson Center Impact Department

When 62% flashes across my mind, I immediately interpret it as a grade “D”. Not stellar, though my 9th grade Algebra teacher might have been stoked to see a result like that on my tests once in a while since I was no “mathemagician”, per se.

But numbers don’t tell us the story, or any story at all. They tell us where to look for the story—and the story within the story. Data is fun this way, isn’t it?

This year, we launched our very first bi-annual TCC 4.0 impact reports to Denver, Douglas, Weld, El Paso, and Boulder Counties, as well as the rest of the Denver Metro area counties in Colorado. TCC 4.0 is a monitoring and evaluation framework that allows us to peer into our programs and uncover areas of strength, identify lessons learned, and hold ourselves accountable to the children, families, and communities we serve. Upholding the framework is an ever-evolving process that must remain as fluid and dynamic as the children we serve in order to empower leaders to consistently provide nothing short of the best possible care for our valued community members.

Our first TCC 4.0 report covered October 2018 – March 2019, and helps illuminate the healing journeys of the typical Tennyson child (and family) engaged in treatment. We see the journey in three non-linear phases: stabilizing, healing, and reintegrating. The final outcome we seek is for children and families to have the resources they need for the long haul, and support them in becoming fully integrated members of their community. These specific goals are important; mental and behavioral health is a journey, not a destination.

American healthcare typically functions in a “disease management” model, but our children do not. Unlike purely physical medical healing, where the journey begins with diagnosis and prescription and ends in healing, our clients’ healing journey requires a lifelong commitment to accepting the past and the trauma they’ve experienced and remaining mindful that, at different life stages and moments, symptoms will present themselves that require seeking help in order to stay well.

The children and families we work with have experienced a lot already. On average, a typical Tennyson child has been through 8-10 placements prior to engagement with Tennyson, experienced at least 4 Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs)—with Colorado experiencing higher rates of sexual abuse and neglect than the national average, and have complex trauma related symptoms exacerbated by a myriad of mental health diagnoses including PTSD, Reactive Attachment Disorder, anxiety disorders, oppositional defiance disorders, and others.

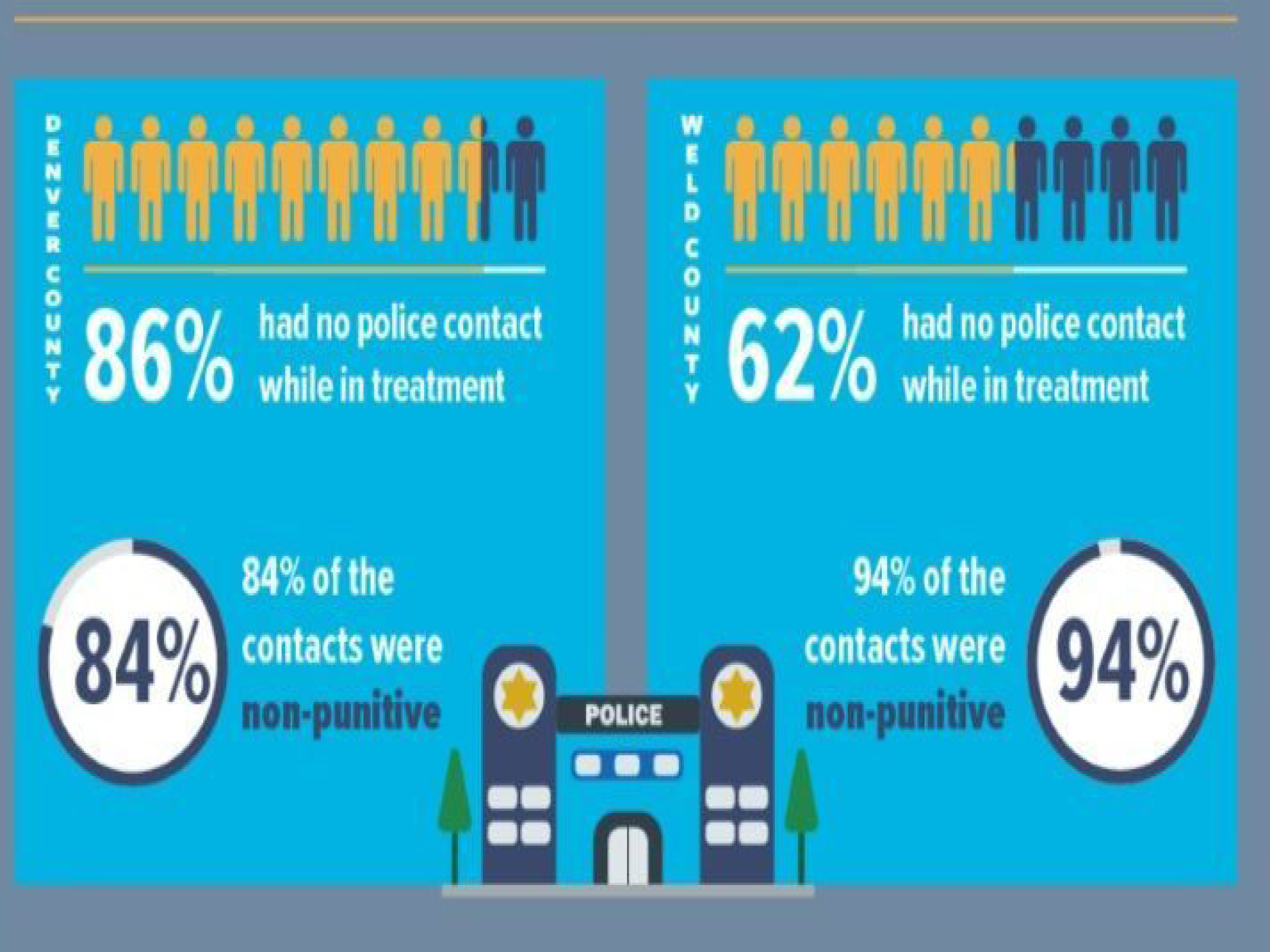

After compiling our first set of results from our inaugural run of TCC 4.0, we gathered our internal team and County partners together to explore the data. In this initial set, something sharply jumped out at us from the Weld County team: why was there such a large comparative difference between police contacts in Weld County vs. other counties, like Denver? Are we doing something wrong in Weld County? Have we missed the mark? But, as we’ve said, numbers aren’t the whole story—they only point to it.

Weld county is a rural, agriculture, and energy industry based county that sprawls nearly 4,000 square miles of northern Colorado with some 315,000 residents. The US Census Bureau calculates that Weld County houses 63 people per square mile. As a point of reference, Denver County, just 30 miles south, has a population of 3,922 people per square mile–there’s more space in Weld county between people. Much more.

The physical distance between people in Weld makes it difficult for residents to connect with resources, access care, and build tight communities. What we discovered in our deeper dive is a story that is as pleasant as Barney Phyfe from Mayberry. People in Weld County predominantly see law enforcement officers as key members of the community: the peacemakers who protect and serve and, at times, lean in closer when someone needs a little more attention.

The fact that residents in rural communities seek law enforcement engagement over those in metropolitan areas is confirmed nationally. “Persons residing in cities with a population of 1 million or more persons (14%) were less likely to have contact with police than those residing in cities or towns with fewer than 100,000 persons (22%).” (BJS)

In Weld County, it is not uncommon for police officers to check in on Tennyson kids from time to time to see how they are doing. One of our clinician remembers an officer who would stop one of our children when he found him wandering out on the road. The officer knew the child was in treatment, knew the family was working very hard, and subsequently pulled up to check in on the child when he’d wandered off after a conflict at home. The visit ended with the child returning home and starting over with mom again. The situation repeats itself as much as necessary because the child matters and the family matters. The Weld police officer exists to protect and serve—in many ways, outside the paradigm of responding to criminal behavior.

__The Deeper Dive into 62% __ While 62% of Tennyson’s Weld County kids had a law enforcement engagement, nearly every single instance (with the exception of one) was a non-punitive interaction—nearly all of them (17/18)! The real story is one of a community seeing our children and walking alongside them through their healing journey.

Why do we call the police? Police predominantly make situations better: “More than 9 in 10 (91%) residents who contacted police to request assistance said they were more or as likely to contact police again in the future. The vast majority (83%) of residents were satisfied with the police response during their most recent contact and felt that police responded promptly (83%) and behaved properly (89%). More than half (59%) indicated that police improved the situation.” (BJS)

Why do our families call the police? Police calls are part of our families’ safety plans. In the event that a child is so escalated that their safety or the safety of others is in jeopardy, a call to law enforcement is the safest, most appropriate one to make. Our children often exhibit extreme, trauma-related behaviors. In these instances, parents are instructed to notify police to ensure the safety of the child, the safety of family members, and the safety of the community. Emma Knutson, LCSW, a Tennyson Center Clinician, shares that, “The key for our families is the get to a point where their lows aren’t so low, and their highs aren’t so high. We want them to be able to calm the child down with skills and tools we provide, and we want the child to learn how to manage their anger, frustration, etc. At times, with the trauma these children have experienced and their subsequent behaviors, calling for help is ok.”

Emma, who predominantly works with Denver Metro area families, reports that when officers arrive on the scene and the safety of the home allows, the officers “wait outside and reinforce our therapeutic work with the family; their presence really encourages safety.” Denver PD’s responses align similarly with our ecosystem of care: 84% of the police engagements (37/44) in Denver measured over the same period of time were also non-punitive contacts, which tells a story of how important a resource law enforcement is to our community, to our children’s safety, and to their healing journey.

Partnerships like these, with law enforcement and first responders, are critical to our approach in building an ecosystem around the children and families who need us most. We are thankful for our law enforcement partners and other care providers in our communities who play a role in ensuring that our children experience changed lives and a renewed hope for bright futures.

And that is why 62% makes us excited!

Brandon Young

Works Cited: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpp15.pdf https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/denvercountycolorado